“Pulsating with Life”: Young British

Artists and the Great War

- David Boyd Haycock

_______________________________

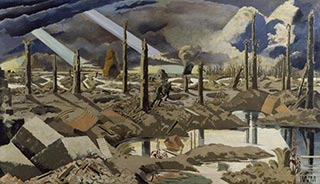

Many of the works begun at the Front were completed in his studio in a state, wrote Margaret, of “fevered tension” [42]. He also began painting in oils for the first time, and produced his first lithographs since his student days before the Slade [43]. His work changed and grew under the stimulus of the War and what he had seen and experienced at the Front; in the fullest sense, he became a Modernist. A Farm, Wyschaete, Ruined Country: Old Battlefield, Vimy, near La Folie Wood, and We Are Making a New World were among the works Nash exhibited in May in a show titled “Void of War”. The writer Arnold Bennett provided an “Introductory Note” to the accompanying catalogue:

Lieutenant Nash has seen the Front simply and largely. He has found the essentials of it – that is to say, disfigurement, danger, desolation, ruin, chaos – and little figures of men creeping devotedly and tragically over the waste. The convention he uses is ruthlessly selective. The wave-like formation of shell-holes, the curves of shell-bursts, the straight lines and sharply-defined angles of wooden causeways, decapitated trees, the fangs of obdurate masonry, the weight of heavy skies, the human pawns of battle, – these things are repeated again and again, monotonously, endlessly. The artist cannot get away from them. They obsess him, and they obsess him because they are the obsession of trench-life. … They seem to me to have been done in a kind of rational and dignified rage, in a restrained passion of resentment at the spectacle of what men suffer, in a fierce determination to transmit to the beholder the full true horror of war. They are in an extreme degree educational; they are bound to educate everybody who sees them – statesmen, diplomatists, newspaper-readers, parents at home who can make nothing out of their sons’ hasty scrawls from the Front. But they are more than educational. Their supreme achievement is that in their somber and dreadful savagery they are beautiful. They give pleasure. We want to carry them away and possess them [44].

Nash’s official war works were well-received by most critics. ‘In his pictures he is usually a romantic artist with a very definite convention,’ wrote the critic for The Times, but “in these works his romance has turned to irony”:

This is a beautiful and wonderful world, he seems to say; and see what man has made of it. See also how even man’s insanity cannot rob the tortured and battered earth of its beauty. In many of his drawings he has been struck by the strange, unaccountable beauty of the meaningless shapes of things so tortured and battered. They make an abstract music of their own, like that abstract music of form that the cubist tries to make for himself. Mr. Nash has not had to make it; it was there for him to see; utter chaos, as of a world dead for a million years, frozen and without atmosphere, and yet beautiful to frightened human eyes. You feel that it has been seen with frightened eyes, eyes frightened at the inhumanity of it. It is waste – the waste of worlds, of ages, which look as if it had been made by some indifferent will of Nature. And then we remember that it has been made by man in his babyish will to power. That is the effect these drawings have on us. They, like all good drawings of the war, might be used in the propaganda for a league of peace [45].

One of the most perceptive critics was P.G. Konody. “Mr. Nash has approached his subject in the spirit of a true artist”, Konody wrote in The Observer. “He does not attempt to rival the camera, but adopts a powerfully synthetic method eminently suitable for the rendering of this inferno on earth” [46]. Konody recognised the literary influence on Nash. “His vision is Dantesque”, he declared. “Again and again his pictures recall the powerful imagery of the third canto of the “Inferno”. There is scarcely a drawing or painting in the collection that does not suggest … the general oppressive horror of Dante’s infernal landscape” [47].

Like Nevinson, Nash had been told not to paint the dead, but many critics subsequently saw the destruction and violation of the landscape as a metaphor for the effects of the war upon its combatants. “Mr Nash’s is an agonized vision”, declared The New Statesman. “He seems to feel in himself the cruelties wreaked on the landscape, the wounds of the amputated trees… the torn wire entanglements writhe on their posts in the pitted ground like symbols of fantastic torment” [48]. Certain detractors, however, pointed to what they considered naiveté in these war works: in 1919 a passing reference in The Observer, whilst noting that Nash “had now become a regular cult”, pointed out that he “was scoffed at and ridiculed a year or two ago” [49]. Konody came to his defence: “If Mr. Paul Nash’s art is nursery art, as has been asserted by unimaginative people with a taste vitiated by an overdose of the Royal Academy, then let us have nursery art by all means” [50]. These were drawings and paintings made in a frenzy of passion. They were images that would endure as among the most sublime and terrifying and beautiful ever made of the Western Front. “I know of no works of art made by any artist working there who saw the splendours and miseries of the greatest of all theatres of war so grandly”, wrote the critic John Rothenstein in 1955. “Out of infinite horror [Nash] distilled a new poetry. The best of them will take their place among the finest imaginative works of our time…” [51].

Nash and Nevinson would join a small number of other artists in producing large works for a proposed Hall of Remembrance that would commemorate the War. John Singer Sargent’s Gassed (1918, Imperial War Museum) would become the most famous of these works, though Nash’s Menin Road (1918-19, Imperial War Museum, fig. 3) was also a remarkable tour de force in oils for an artist who until very recently had painted almost exclusively in watercolours. Nevinson’s painting, The Field of Battle, however, eschewed the Futurist techniques that had made him famous, and was one of thel least successful contributions to the series – for a monument that would, in the end, never be constructed.

The government’s official war artist scheme had provided a lifeline for both art and artists, and would be copied by a similar programme of record, propaganda and memorial run by the Canadian government. As well as Nash and Nevinson, the younger participants in either one or both of these schemes included David Bomberg, William Roberts, Stanley Spencer, Percy Wyndham Lewis and Nash’s younger brother, John. As well as producing one of the greatest schemes of officially sponsored art in history, these two schemes also gave artists hope at a time when the future seemed to offer none. “This is excellent!” Mark Gertler told Lady Ottoline Morrell after he received a commission from the government to paint an official picture of the home front in 1918:

There is a good time coming for Art yet in England, no it shan’t always be French, French, French … This Idea – I mean this War Memorial Committee, has somehow excited me very much! Because I see so much, that is significant in it. I am ambitious about having a really good school of painting in this country. I am sick of it always being French. Yes, about painting I am patriotic! What’s more, I have a feeling that we are going to have good painting, after the War — there are good times coming if only we can hold out. This War is not the end [52].

For a moment, Gertler’s prediction seemed to hold true. Shortly after the Armistice in 1918 the prominent New York collector Albert Eugene Gallatin visited Europe, and was fascinated by what he saw in London. “Pulsating with life and possessing a distinctly fresh vision”, he told an interviewer from The Observer in 1921, “a movement is now well under way which, in my opinion, will develop into one of the great epochs of English painting. Paris and New York cannot in this respect vie with London” [53]. This new vitality had its origins immediately before the war. It had then been interrupted by the war, before being reinvigorated by it. Sadly, its promise was not fully realized. C.R.W. Nevinson had his moment in New York, when that city seemed to promise him a way forward, to maintain the momentum from the war, but it was not to be. David Bomberg was forced abroad, travelling to Palestine, and later to Spain, to pursue his remarkable vision. Gertler’s star never shone so bright again, and it would be many decades before London really did vie with Paris and New York to hold the crown of contemporary art. For a moment, however, it had seemed that it was here, in England, out of the horrors of war, that Western art’s future might really lie.

[42] Margaret Nash (1951), op cit., f. 20-21.

[43] Andrew Causey, Paul Nash: Paintings and Watercolours (London: Tate Gallery, 1975), p. 58.

[44] Arnold Bennett, ‘Introductory Note’, ‘Void of War.’ An Exhibition of Pictures by Lieut. Paul Nash (Ernest Brown & Phillips, London, 1918), pp. 4-6.

[45] The Times, 25 May 1918, p. 9.

[46] The Observer, 14 July 1918.

[47] The Observer, 19 May 1918.

[48] The New Statesman, 13 July 1918.

[49] The Observer, 2 February 1919.

[50] The Observer, 14 July 1918.

[51] John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters, Sickert to Moore (London: Eyre and Spotiswood, 1957), pp. 347-348.

[52] Mark Gertler to Ottoline Morrell, 24 April 1918, HRRC.

[53] The names Gallatin picked out for notice included Nevinson and Nash, Augustus John, William Orpen, Wyndham Lewis, John Nash and Stanley Spencer ; The Observer, 26 June 1921.