Representing Evolution: A Case Study

in Visual Narrative

- Richard Somerset

_______________________________

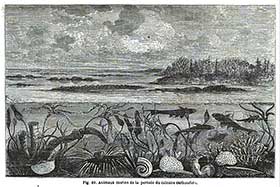

Fig. 1. Ed. Riou, “Animaux marins de la période du

calcaire carbonifère”, La Terre avant le Déluge, 1864

Fig. 2. Ed. Riou, “Vue d’une forêt et d’un marécage

pendant la période houillère”, La Terre avant le Déluge, 1864

The ‘History of Life' genre

The mid-nineteenth century saw the emergence of the ‘History of Life', a genre that situated itself tantalisingly astride a number of frontiers, combining elements of antiquarianism, the exact sciences and the fantastic journey. It was created in response to the particular characteristics and potentialities of the ‘historical sciences' of geology and palaeontology, young disciplines that had struggled to find a clear-cut place amongst the established physical sciences. The main issue was a certain discontinuity between the field’s ostensible methodology – which had to be strongly empirical to justify the appellation of ‘science' – and the sorts of results that it promised, which were decidedly historical in character. In theory, the hope was that the empirical study of the earth’s strata and the fossilised remains they contained would permit practitioners reliably to reconstruct the pre-human story of life on the surface of the earth. However straight-forward this programme might sound to an age accustomed to historicist thought, the fact that the achievement of the desired outcome depended upon a willingness to shift, at some stage, from an empirical to a narrative frame of reference inevitably raised the question of the field’s scientific standing.

So the characteristics of the emerging domain made it both exciting and problematic. It was exciting for its capacity to open up hitherto unguessed-at perspectives of an immense material history unarchived in human records and inhabited by creatures unexampled in human experience; and it was problematic because the very strength of its narrative potential effectively undercut the credibility of its scientific aspirations. Clearly some sort of compromise strategy of narrative management would have to be found.

In the very early days, a naturalist such as Georges Cuvier had been able to straddle the divide by producing, in separate spaces within the same work, both substantial empirical material and a sustained geohistorical interpretation of those findings [1]. But as the field became more specialised and professionalised, this dual function became harder to carry and practitioners were increasingly limited to one or other role. This left a space open to the popularisers, who produced the ‘History of Life' genre in response to the retreat of the specialists. Writing avowedly for a generalist audience, their explicit aim was to render an important technical subject thrilling by ‘translating' the scattered findings of the scientists into a unified natural narrative. Thus occupying the critical space of interaction between the scientific and the historical legs of the discipline, it was well-placed to ventilate the discipline’s core debates – and to attempt to naturalise fixist or evolutionist understandings of nature’s historical processes.

The genre’s benchmark was established by the French scientific populariser Louis Figuier in his 1863 publication, La Terre avant le déluge. He was himself responding to the somewhat whimsical – and now almost completely forgotten – Paris avant les hommes published by Pierre Boitard in 1861, which had used the conventions of the fantasy tale to allow the protagonist to follow, in a dream-journey, the historical stages in the development of life. Boitard had exploited implicit parallels between different continuities: the conventional continuity of narrative on the one hand – the story of the traveller passing successively from one scene to another – and the ‘real' continuity of natural historical processes on the other. The plottedness of the protagonist’s journey spills over into the domain of nature, transforming a space of categorial fixity into one capable of responding to a logic of change and development. Figuier’s response, designed to counter this developmentalist outlook, used similar tools in a very different way, resulting in a studiedly empirical text that also followed the course of geological time, but did so in the form of a rationally distanced account mediated by a disembodied narrative voice. Figuier’s ‘journey through time' was virtual and rational in contrast to the materialised fantasy of his counter-model, Boitard.

In order to defend a fixist model of natural history, Figuier selected and presented his material in such a way as to suggest that the story of Life was typified by a series of distinct creations. Each stage in the story constituted a step up on the earlier one, but that sequence was not to be understood as resulting from a naturalistic process of development. Since developmentalism was predicated upon a process of natural and therefore gradual change, Figuier countered it by offering a narrative of discontinuity; one that sought to stress at every turn the differences between the successive ‘worlds' of the geological past.

Figuier’s main writerly difficulty resided in the challenge of arranging his voluminous empirical material in such a way as to produce the right sort of narrative. He needed to find a way to ‘place' his mass of facts within a framework of underlying narrativity that would permit the reader to make sense of them, while avoiding the danger that the narrative might come to dominate – and so give unwanted weight to the feeling that Nature herself was characterised by an analogous narrativity. Figuier therefore sought to control and direct the narrative energy of his account by separating out the descriptive or empirical work on the one hand from the narrative work on the other. While the empirical content was carried by the main text and its accompanying specimen illustrations, the narrative was essentially carried in a separate space, embodied by a series of special illustrations that Figuier called “Ideal Scenes” [2]. These scenes appear throughout the text, one or two per chapter, and serve to encapsulate in a single living ‘moment' the world as it was supposed to have been at the particular age in question. Illustrations being intrinsically static, in contrast to the implied movement of narrative, they could readily be used to give expression to the dynamic of discontinuity that was so important to Figuier.

Take for example these two ‘Ideal Scenes', representing consecutive stages of the carboniferous age, appearing a mere twelve pages apart in the text (figs 1 and 2) [3]. It is immediately striking how radically different these scenes are from one another; despite their relative proximity in time, they seem to represent quite different worlds. Similarly, a number of subsequent scenes contain wondrously exotic beasts which appear only once and then disappear to be replaced by other equally weird beings of a completely different kind. Thus the extraordinary exoticism of these scenes, along with the immense variety of landscapes and living types represented, served at once to maintain the reader’s interest and to naturalise a guiding narrative of discontinuity in nature’s affairs.

[1] Cuvier’s four-volume Recherches sur les ossements fossiles (1812), for example, was an unprecedented empirical survey of extinct vertebrate species. However, its ‘Discours préliminaire’ was considered such an important reflection on the nature and the import of the study of the pre-human past that it was soon published as a separate pamphlet, first in English translation as the Essay on the Theory of the Earth (1813), and later in French as the Discours sur les révolutions à la surface du globe (1825). For an account of the importance of Cuvier’s text, and the inaccuracies of the initial English translation, see Martin Rudwick, Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008, pp. 20-22.

[2] They were executed by Edouard Riou, a successful illustrator of popular literature. He also worked with Jules Verne during this period. See Martin Rudwick, Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992, pp. 173-218 for a detailed discussion of Figuier’s illustrations; and the book as a whole for remarks on early pictorial representations of the geological past.

[3] These illustrations first appeared on pages 91 and 103 of the 4th edition of 1864.